Updated: 2009-10-22 08:56

Beijing-based cultural critic Tan Fei says he has a new addiction called wei bo or microblogging.

It all started a month ago when he was invited to join the team testing Sina Weibo, a Twitter-like service launched by China's portal giant Sina.com.

Tan admits that despite being an active blogger, he had little idea about Twitter or microblogging.

Nowadays, while driving, Tan says he has to pull over whenever he feels the itch to type his thoughts on his mobile phone, send them online and share them with hundreds of his followers or fans with a click.

"I've taken to wei bo and I simply have to readjust my pace to fit it into my routine," Tan says. "It is addictive."

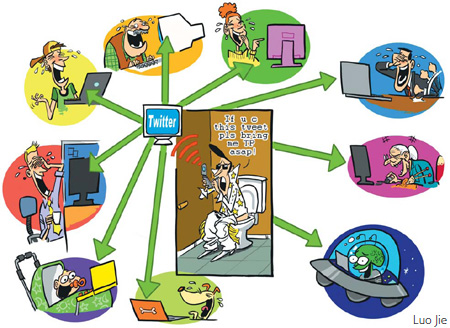

Like Twitter - the world's leading micro-blogging service - Sina Weibo allows users to post short messages, or "tweets", less than 140 Chinese characters long via website, SMS or MMS. These can be shared or forwarded immediately by those who follow a blogger's updates.

Within a month, Tan has updated more than 360 tweets, about a dozen a day, which are followed closely by more than 5,000 fans.

Tan is not alone.

Meng Bo, deputy editor-in-chief of Sina.com and project manager of Sina Weibo, says that over the past two months, they have observed encouraging feedback from new users, although he declines to give specific data, saying "the service is still undergoing testing".

"They love Weibo. That's good news," says Meng, adding that Sina has been preparing to launch the service as it represents "the future of media and communication".

At a time when Twitter and its popular Chinese incarnations - Fanfou, Jiwai and Digu - are inaccessible for various reasons, such a feedback is encouraging not just for Sina, but also for the growing micro-blogging community.

Since Twitter debuted in 2006, the population of Chinese microbloggers has been rapidly on the rise. The growth has been accelerated by the launch of home-grown Twitter-esque services, Fanfou being the best example.

Dubbed China's Twitter, Fanfou was founded in July 2007 by Wang Xing, a 29-year-old entrepreneur who runs two other successful social networking websites Xiaonei (for college students) and Hainei (for white-collar workers). By the end of June, Fanfou's registered members reached nearly 1 million, or a quarter of Twitter's worldwide users.

While Twitter became mainstream in 2008, critics have expressed concerns about the future of microblogging in China, considering the country's relatively strict Internet regulations.

Such skepticism mounted in early July as Twitter, Fanfou and two other popular microblogging services - Jiwai and Digu - became inaccessible. It is commonly believed that the services had been used to spread misinformation about the unrest in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

None of the websites is yet available again. Wang says that he "is still working on" bringing Fanfou back as soon as possible.

"The launch of the new service by Sina, the first by a major Web company in China, means micro-blogging is here to stay," says Hu Yong, an expert on new media from the School of Journalism and Communication of Peking University.

"Thanks to its brand influence, Sina might be able to popularize this trendy Internet service in China and determine the direction of its future development in the country," Hu says.

But it is far too early to tell if Sina Weibo will become such a platform.

The suspension of Fanfou makes one thing clear - a 100 percent Twitter clone won't survive in China, Hu says.

That may not be a big problem for Sina, owing greatly to its more than 10 years of experience in content monitoring, Meng says.

Sina is playing by the rules as they are laid down, with strict word filtering in operation, he says.

"From the very beginning, we're determined to develop a micro-blogging service with Chinese characteristics," Meng says.

"We've put in place two teams of staff keeping close watch to ensure there is no vulgar content or anything that violates the rules on Sina Weibo. We're also ensuring its interactive functions."

However, a monitoring system might compromise the free flow of real time information, which is the very essence of microblogging. This has proved a problem for Sina Weibo.

Ever since its debut tests, there have been complaints and derisive comments from seasoned twitterers and former Fanfou users.

One of the most popular tweets on Twitter goes: "Weiboers don't know anything about Twitter, but Tweeters know that Weibo is nothing compared with Twitter."

Tweeter Ran Yunfei, a Sichuan-based journalist in his 40s, says that Weibo might be a Twitter clone in appearance, but its control on content deprives it of the Twitter spirit.

However, Ran welcomes Sina Weibo - a service that he says "helps facilitate information flow".

What Sina has lost in seasoned tweeters, it might win in new users thanks to its strong marketing, as demonstrated by its success in building its blogging service into the country's top blogging platform.

With nearly 40 million bloggers, or 47.5 percent of the country's blogging population, Sina ranks first in China, according to a September report by CR-Nielsen.

By inviting celebrity bloggers, such as film star Jackie Chan and actress Xu Jinglei, Sina has overcome its disadvantage as a late-comer in the blogging market and has grown rapidly.

Sina Weibo seems to have adopted the same strategy, already reaping similar dividends. The No 1 microblogger with more than 140,000 followers at Sina is Huang Jianxiang, 41, a former sports commentator with China Central Television and anchorman at the Hong Kong-based Phoenix Television.

While Sina hasn't revealed specific numbers, Meng says microblogging is "growing fast", mainly because of first-time micro-bloggers.

However, experts agree that it is still too early to tell if Sina Weibo will survive.

Striking a balance between the country's Internet regulations and users' increasing demand for speedy real time information is like "tightrope walking", says Hu.

(China Daily 10/22/2009 page18)